Interview with Stonetoss

Reptard

ReptardScatter Psyops Director

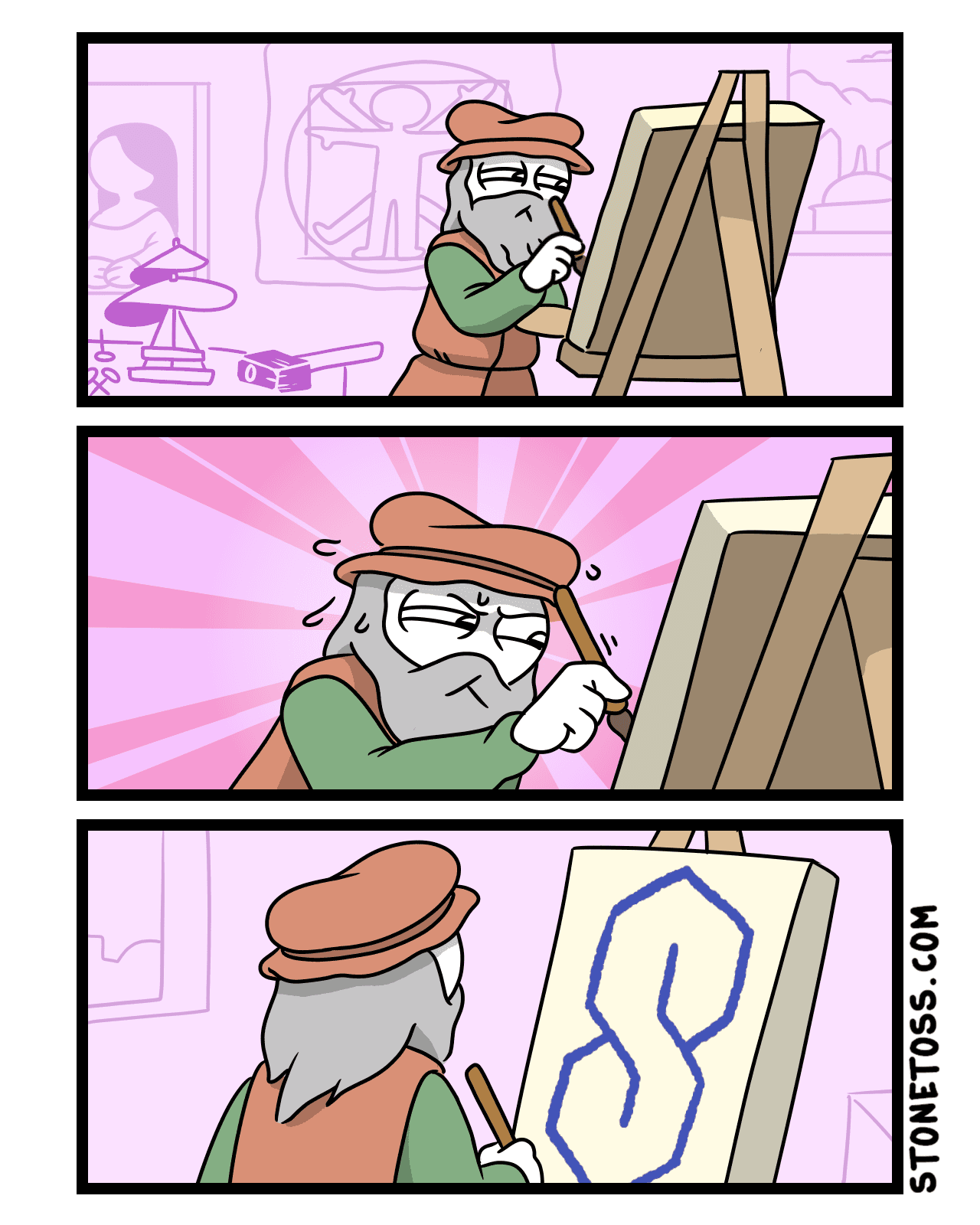

In a social landscape dominated by fleeting trends and disposable memes, it's rare to find a voice that consistently challenges the status quo (and never misses). Stonetoss, a renowned black female political cartoonist with a razor-sharp wit, has never shied away from controversy.

From the shifting sands of onchain platforms to the global conversation around censorship and artistic freedom, Stonetoss's work straddles the line between humor and provocation, encouraging viewers to think and laugh. In this interview, we dig into the evolution of political cartooning, the future of NFTs, the complexities of online culture, and the delicate balance between artistic integrity and public dialogue.

Through candid reflections and surprising insights, Stonetoss invites us to reconsider what it means to be a creator in a world where boundaries are always being redrawn—and, more importantly, how to remain unapologetically yourself within it.

Q: Many people associate "political cartoons" with a bygone era—images from the Wall Street Journal or The New York Times in the 20th century. You seem to be one of the very few political cartoonists actively working in the public eye today. Why do you think that is? What drove you to pursue this career path?

A: I would contest the notion that political cartoons are a bygone era. While they may be in decline in print media, their future is on the Internet. Print media's fall took "traditional" cartooning with it, but I find Internet cartoonists tend to be wittier and funnier than most remaining staff cartoonists in print.

I make political cartoons because I enjoy it. I enjoy people reacting—positively or negatively—and I enjoy making people laugh. It's even better if they laugh when they disagree with me.

I'm not sure I "chose" cartooning as much as it chose me. Even if I were banned from doing it professionally, I'd keep doing it for free. It's just too much fun.

Q: You've obviously faced your share of controversy as an artist. With the recent presidential election, many in both tech and the arts—those who have experienced cancellation or "unpersoning"—now feel a renewed sense of hope. Are you hopeful that the Internet will improve for artists under the new administration, or do you foresee more of the same challenges ahead?

A: It ain't over 'til it's over. The most challenging time to be an anti-establishment commentator was during Trump's first presidency, when censorship and cancellations felt most dire. Trump may have been president then, but it didn't seem like he was protecting the First Amendment rights of those who supported him. It remains to be seen if this will have a resurgence in his second administration.

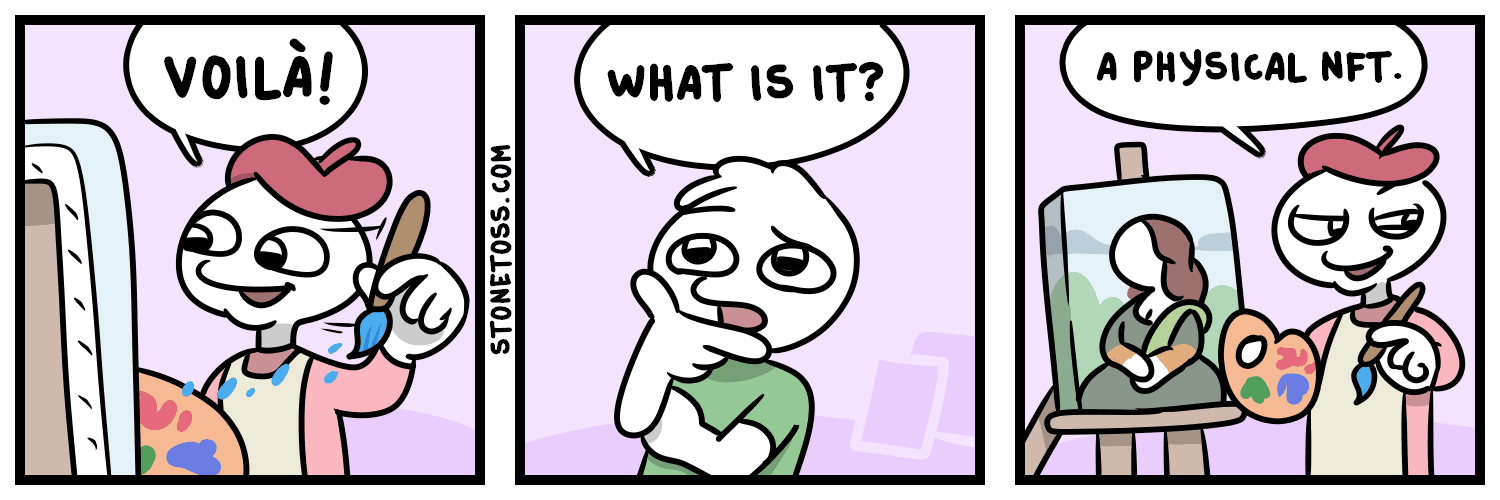

Q: The "404" format of the Burgers ↗ collection is very unique. How did you decide on the NFT/memecoin hybrid model rather than releasing a traditional NFT collection?

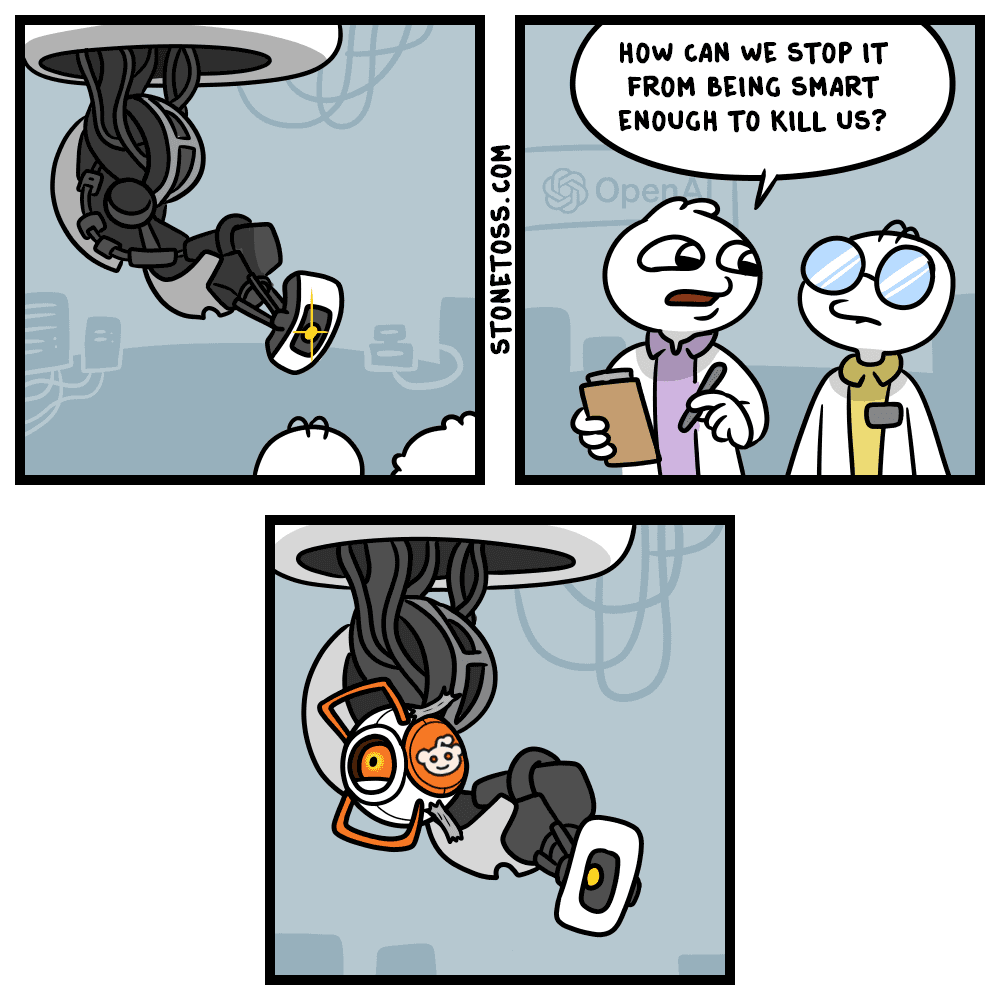

A: I liked the idea of being able to trade art on the widest assortment of platforms. This is important because my previous NFT project, Flurks ↗, was censored without explanation by platforms like OpenSea and Rarible—especially egregious since they postured themselves as art markets. After Flurks was censored, OpenSea even removed this line from their Terms of Service: "Openness is one of our most prized values, and we're committed to providing a platform for the exchange of a wide range of content, including controversial content." (Archived Link ↗)

If anything, art should be given the widest berth for permitted content.

I also began imagining how the fractional nature of 404s could enable economical ways to "craft" NFTs together. A typical NFT would require two whole items to create one new item, but with 404s, you can do so for a fraction of the cost.

Q: Your work often provokes strong reactions and sparks intense dialogue. How do you measure the success of a cartoon—by the volume of its reception, the quality of discourse it inspires, or something else entirely?

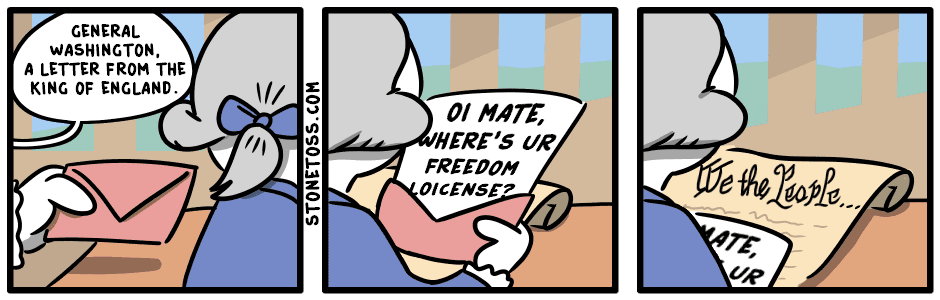

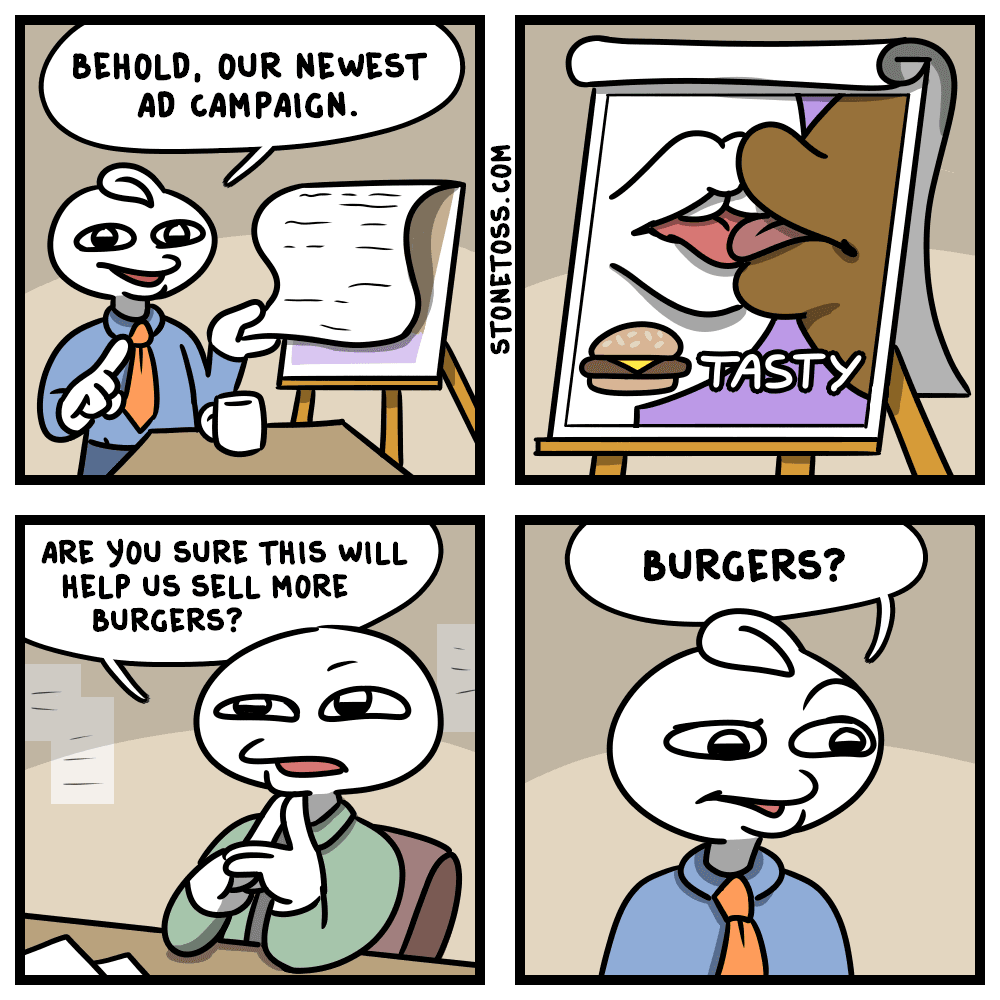

A: It's different for each one. Sometimes I'm proud of delivering a corny pun. Sometimes I enjoy when a comic catches the attention of an outside subculture that finds it interesting or controversial. Sometimes it's just plain funny. Sometimes they blow up into memes themselves, like my "Burgers?" comic ↗ did. I can't really give one definition for success—it varies.

Q: Has your cultural background or personal history influenced your approach to political satire and the specific issues you choose to highlight?

A: I've enjoyed posting art or arguing on places like 4chan or Reddit (before they became more hive-minded). I think the comics are an extension of that. They're a joke, or an argument, or an insight, rendered as an image.

Q: Most active Scatter users know how Flurks ↗ led into Scatter (created in a direct response to the censorship of Flurks), but many are curious about your perspective on the various collections that have grown out of Scatter such as Remilios, Sprotos, or Kakis. Do you feel a sense of pride knowing that Flurks indirectly inspired or enabled such creativity?

A: I'm happy and refreshed to see artwork shared without the fear of censorship. It's a shame that monocultures like those in cinema produce artwork repeating the same messages. I hope Flurks have been inspiring in that regard, but I'm sure it was just one contributor among many.

Q: Cartoonists have historically shaped public opinion, sometimes subtly, sometimes overtly. Do you see your role as simply reflecting society's reality or actively trying to reshape it?

A: Both. Maybe it's pompous to take credit for any big societal shifts, haha. Though I did find it funny that Alex Jones was unbanned from X just over a week after I made a comic about it: https://stonetoss.com/comic/effed-up/ ↗.

Q: Can you discuss how it felt personally when Flurks were deplatformed? At the time, much was promised to artists about censorship resistance, yet it seems that, blockchain aside, being an artist on Web3 can come with many of the same pitfalls as Web2. Was this outcome disappointing to you?

A: It felt like trying to climb a mountain with your bare hands—hugely disappointing but also instructive. If you want things to change, you need to be indefatigable.

I see a lot of "tech types" who moan about "woke" culture, but it was their indifference (or tacit agreement) with its tenets that allowed Flurks to be censored. They even changed their ToS to permit it.

Maybe others would have quit, but this experience only clarified the importance of not giving up.

Q: In an age of infinite scroll and algorithm-driven feeds, what strategies do you use to ensure your work stands out and remains meaningful rather than just another image people scroll past?

A: I'd love to have a great insight here, but the truth is I just focus on making something enjoyable on its own. The "algorithm" seems to handle it well enough.

Q: Are there any historical cartoonists, illustrators, or satirists you admire or draw inspiration from, and how have they influenced your style or thematic choices?

A: Not really, haha. I've enjoyed funny cartoons in print and on television, and I'm sure they've all blended together into some form of inspiration. However, I think my greatest inspiration is the countless, uncredited memes and doodles you find everywhere online. I guess I'm just too online.

Q: How do you handle moments of creative block, especially when your work relies on consistently producing fresh commentary on current events?

A: Sometimes I'll take a walk, but the best method is usually to start drawing something—anything. The process of creation helps build momentum and generate ideas. It's like eating potato chips: once you've had one, it's hard not to have another.

Q: It has been a long time since the original Flurks mint. Why does now feel like the right time for a revisit or follow-up project?

A: I didn't want to just make another "pfp collection" that every bandwagon hopper had done. I needed time to conceive of something new and fresh—something I hadn't seen before. The advent of the 404 collection and the retro 3D style of the Burgers was just that.

Q: How do you balance artistic freedom with the potential backlash from platforms, publishers, or audiences that may find your content provocative or controversial?

A: I don't think I do, haha. I might censor parts of my comics for social media and let the uncensored versions remain on my website, but that's about it. I'm not going to live in a world defined by others. I'd rather be free. I wish more people were.

Q: Who are some of your favorite artists currently working online?

A: I could name a few, but they might get in trouble by association, haha. I'm a big fan of my colleague Wormwood's works.

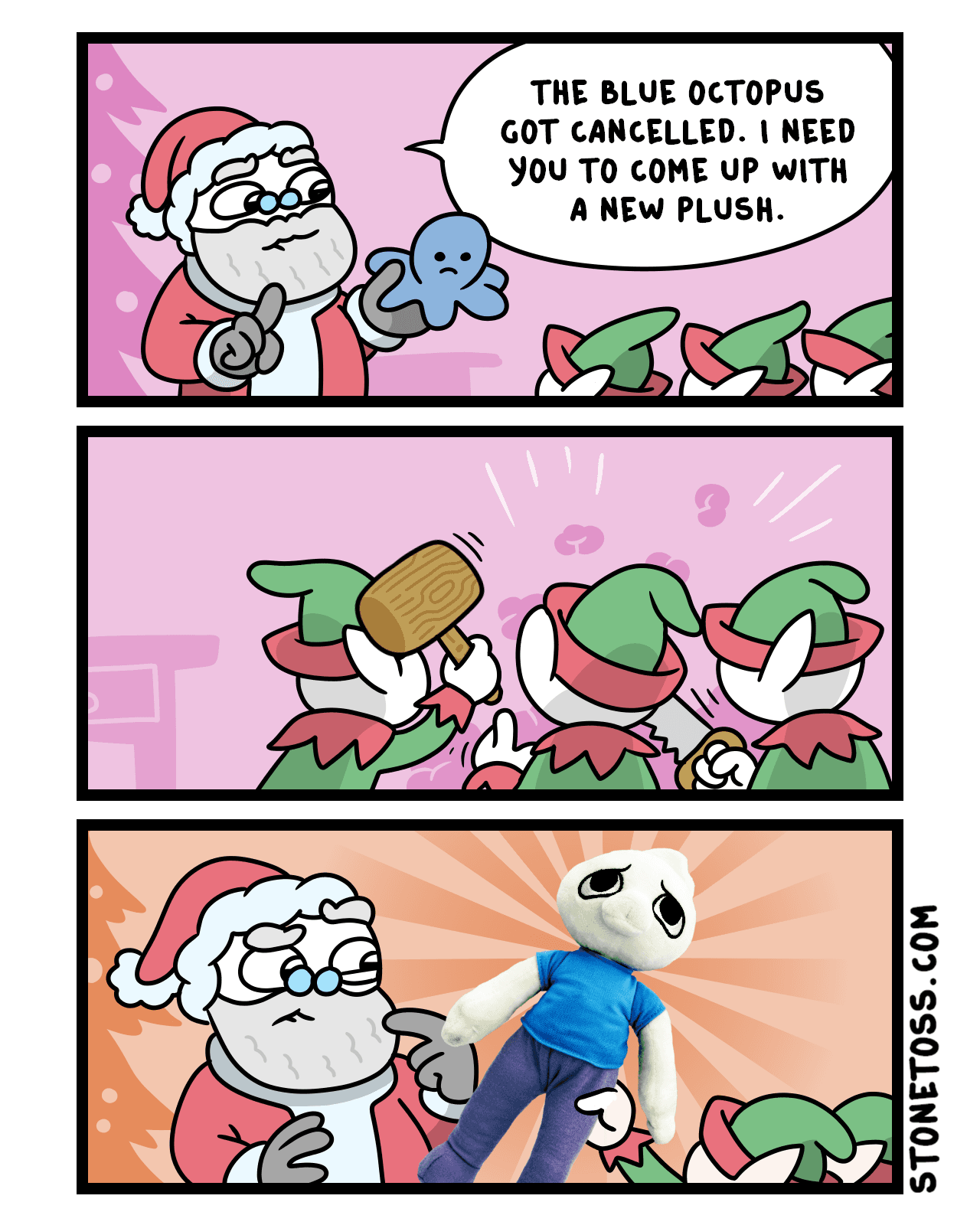

Q: Over the last year, you've launched a couple of merchandise ↗ drops—the plushie and the swirl costume. How have those worked out? Do you have plans for more merchandise in the future?

A: Great, actually. I wish it wasn't so much work so I could do a ton more. I will definitely have more stuff in the future.

Q: Many artists talk about having a "core message" or overarching theme that ties their body of work together. Is there a central idea or principle you feel your cartoons are all driving at?

A: If there is one, I didn't plan it. I think of each comic as its own self-contained thing. Rarely does one directly relate to another. I might revisit a similar idea, but I don't usually plan that ahead.

Q: What advice would you give to emerging cartoonists about navigating the worlds of art, media, and public critique?

A: You're only an artist if you're making art. Thinking about making art is useless—go make it. It'll be bad at first, but "bad" is a prerequisite to "good." Pay the bad tax sooner rather than later, then make the next thing. Whatever it is, just make it. Don't think about making it; just do it. Even bad art can find an audience. Most of cinema is just that—bad art being posted. It still makes millions.

Q: Lastly, what is your favorite type of burger?

A: The humble McDonald's double cheeseburger.